Streambank Erosion and Restoration

Streambank Erosion in the Illinois River Watershed

In the Illinois River Watershed, many farmers, ranchers, and families are losing acres of land every year from streambank erosion; the estimated loss of productive land in our watershed is 20 acres each year. This loss in productive and valuable land results in financial losses to landowners today as well as future generations. Here at IRWP, we are monitoring streambank erosion and providing grants and technical assistance to landowners to reduce erosion and improve land productivity.

Streambank Erosion Assessment Study

Illinois River and Tributaries: Streambank Erosion Sites and Analysis 2020 Report

Since 2017, the Illinois River Watershed Partnership (IRWP) and partners have monitored streambank erosion in the Upper Illinois River Watershed. Through multi-year field measurements and analysis at 15 sites representing around 5% of the watershed, we find that erosion is projected to contribute 102,822 tons of sediment and 154,233 lbs of phosphorus annually into the watershed. Observed streambank erosion is driven primarily by changing land-use as well as increasing precipitation.

View the Brief .PDF

Illinois River and Tributaries: Streambank Erosion Sites and Analysis 2020 Report - Brief

Background

Precipitation has increased and flooding is increasing in frequency and volume over the last decade in much of the watershed. IRWP and partners recognized the need to regularly monitor how the stream system is responding to landscape changes including rapid urbanization and population growth. Annual surveys on 49 miles of streambank were conducted in consecutive years spanning from 2017-2020. Utilizing established methods, we measured yearly erosion rates and calculated Near Bank Shear Stress (NBSS) at each site to develop a graphical prediction of annual streambank erosion rates.

Findings

Streambanks in the upper Illinois River Watershed have eroded on average 3.88 feet of bank annually. Of the 15 study sites, eight have High, Very High or Extreme NBSS which means that high velocity water is concentrated along the streambank during high flows. Erosion is very likely to continue at accelerated rates at these locations. Based on modeling developed from these field measurements, erosion rates throughout the Upper Illinois River Watershed are projected to be 1.01 feet per year across the watershed. Observed streambank erosion is driven by a combination of factors including natural processes, changing precipitation, urban stormwater runoff, deforestation of the riparian corridor, construction in the floodplain, past attempts to alter the stream channel, debris jams, and gravel deposits from upstream bank erosion. Targeting restoration measures that reduce erosion at the most extreme sites could have a measurable positive impact on the watershed. In fact, restoring just the 4 highest priority banks of the 15 study sites could reduce the total sediment loading within the 49-mile study area by 11%.

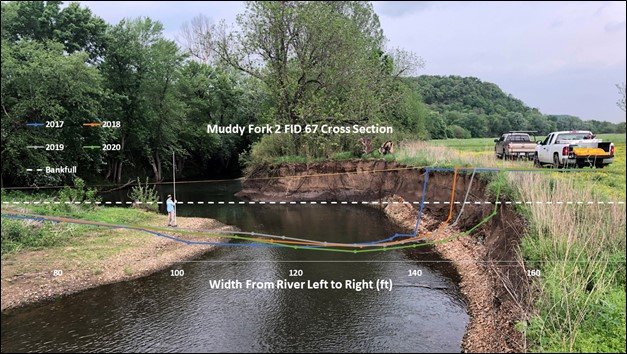

This image shows a cross-section of Muddy Fork, a tributary of the Illinois River, where erosion has left a steep cut bank. The bank and the vegetation are sheared away over time from the volume and velocity of water hitting the channel during rain events.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates the need to address the primary drivers of streambank erosion by developing more comprehensive stormwater management solutions, and maintaining generous riparian buffers in both headwaters and downstream. Maintaining and restoring an extensive riparian and floodplain buffer of native deep-rooted vegetation is critical to the long-term stability of streambanks throughout the watershed. It is our hope that this study will help inform planning as we strive to understand, protect, and restore the water quality and habitat within the Illinois River watershed for generations to come.

According to data collected by IRWP, the average landowner lost 3.8 feet of land annually since the study started and approximately 29% of streambanks will continue to lose at least one foot per year throughout the Upper Illinois River Watershed. These data indicate that we are in the middle of system-wide change that will not only impact the river, but may also impact the economic development potential of Northwest Arkansas as we expand westward into areas of the watershed that are at greater risk for flooding and erosion.

All rivers, creeks, and streams move and erode, but the question is how much of that erosion--and subsequent movement-- is a result of increased water velocity and volume that is preventable. Erosion creates a snowball effect: Loss of vegetation further weakens the banks, making even small amounts of stormwater destructive, loading even more sediment. Trees are wiped out and their branches collect downstream, causing further disruption. With little or no streamside vegetation and with so few roots to keep the soil on the banks in place, the water is exposed to direct sunlight, increasing the likelihood of algae blooms, pathogenic breeding grounds, and subsequently creating safety issues for animals and people. Infrastructure also becomes threatened by the increase in volume and velocity of stormwater, creating public safety hazards and costing landowners and municipalities tax dollars.

Want to begin your streambank stabilization project? A great place to begin is by seeding bare spots on your streambank using a seed mix that includes fast growing plant species. Hamilton Native Outpost sells a Streambank Mix to help stabilize your streambank with fast growing vegetation.

Resource Hub

LAND USE RESOURCES

A Framework for Understanding Conservation Development Patterns

A Guide to Retrofitting Stormwater Ponds

Appendices for Stormwater Detention Retrofits

City of Fayetteville Drainage Manual Appendices

Fayetteville Drainage Criteria Manual

Fort Collins Stormwater Criteria Manual

Streambank Erosion and Restoration Video Learning Center

WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PLAN

Plans for the Illinois River Watershed in Arkansas and Oklahoma

Upper Illinois River Watershed

The Upper Illinois River watershed is defined for this plan as the Arkansas portion of the eight (8)-digit hydrologic unit code (HUC8) 11110103, Illinois watershed. The Upper Illinois River watershed encompasses 758 square miles in northwestern Arkansas (Figure 2.1). A number of cities are located within the watershed, including Fayetteville, Gentry, Prairie Grove, Rogers, Siloam Springs, and Springdale. The largest towns are located along the eastern watershed boundary, Rogers, Springdale, and Fayetteville. US Highways 62 and 412, and Interstate 49, cross the watershed.

The Illinois River originates near Hogeye, Arkansas in Washington County. The river flows westerly, crossing the Ozarks of northwest Arkansas and into Oklahoma approximately five (5) miles south of Siloam Springs, Arkansas, near Watts, Oklahoma. The river continues southwesterly in Oklahoma to Lake Tenkiller and eventually flows into the Arkansas River near Gore, Oklahoma. Other Counties that are part of the watershed are Benton and Crawford Counties (Table 2.1). Washington County accounts for 60 percent of the watershed, and Benton County accounts for 40 percent of the watershed.

The Upper Illinois River is one of the 12 Nonpoint Source Program priority watersheds designated by Arkansas Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Division (Natural Resources Division) in the 2022 (Nonpoint Source Management - Arkansas Department of Agriculture).

There are stream reaches in the watershed that are included in the approved 2018 state impaired waters list (303(d) list) due in part to pollution from nonpoint sources. The update to the Upper Illinois River Watershed Management Plan was initiated in response to the changing landscape of the Illinois River watershed and the current plan was over twelve years old. This updated plan re-evaluates current water quality conditions, re-evaluates target sub-watersheds for implementation of conservation practices, engages existing and new stakeholders, and establishes new milestones for water quality improvement in accordance with US EPA guidance for a nine-element watershed management plan.

Five Category 1 HUC12 sub-watersheds ranked for highest return on investment for conservation practice installation to improve water quality include Moores Creek (11101030102), Lower Muddy Fork (111101030103), Little Osage Creek (111101030302), Lake Wedington-Illinois River (111101030403), and Lake Frances-Illinois River (111101030606). For each Category 1 subwatershed, water quality targets to address nonpoint source pollutants were established. Water quality targets established were for nutrients (i.e., phosphorus and nitrogen), sediment, Escherichia coli, chlorides, and sulfates.

The watershed-based management strategy which considers watershed land use, water quality conditions, and existing and potential pollutant sources, has been approved and accepted by the Arkansas Department of Agriculture - Natural Resources Division and EPA. To meet water quality targets, the Upper Illinois River Watershed Management Plan outlines voluntary conservation practices and anticipated reductions to nonpoint source pollutants. For all six sub-watersheds stakeholders identified between 11 and 16 conservation practices identified for implementation in either rural or urban watersheds, respectively. Voluntary conservation practices range from pasture management techniques such as filter strips and utilization of nutrient management plans to urban practices for stormwater management.

We would like to thank the Arkansas Department of Agriculture - Natural Resources Division and EPA Region 6 for their financial support for the development of this plan. We would also like to thank Philip Massirer, Christina Laurin, Kelsey Criswell, and others at Olsen FTN for their work, among many contributors, in the development of this watershed-based plan for the Upper Illinois River Watershed.

The Oklahoma Watershed Management Plan is expected to be available in mid-2025. It will be posted here once available.

Streambank Erosion: Many of us assume it is a natural process for any river or stream. But that eroded streambank or moving river channel may be due to upstream land use changes. This series of resources discusses why it's happening and what you can do about it.

Overview of Streambank Erosion and Restoration

Natural Stream Restoration: Streams in Nature (Part I)

Natural Stream Restoration: Good Stream Gone Bad (Part II)

Natural Stream Restoration: Restoring Streams (Part III)

Streambank Stabilization and Restoration Case Studies

Why Should You Stabilize a Streambank

Stream Restoration - Illinois EPA

Streambank Restoration Timelapse